THE MORBID AND THE BEAUTIFUL

I will never forget the first time I walked into the rooms of the Munch collection in Oslo. I was twenty-one, poor, haunted, friendless, in a foreign country, a country I had chosen to make my home—in soul-sick, self-imposed exile from America. Lonely as only a young poet can be in a country where he cannot speak the language, I would walk around for days enveloped in a misty cloud of dread, in the grip of a vertiginous anxiety that transformed the harbor streets of Oslo into the smoky mineral light of the Inferno. My forced fundamentalist childhood religion was dying an agonized death. The Void was opening.

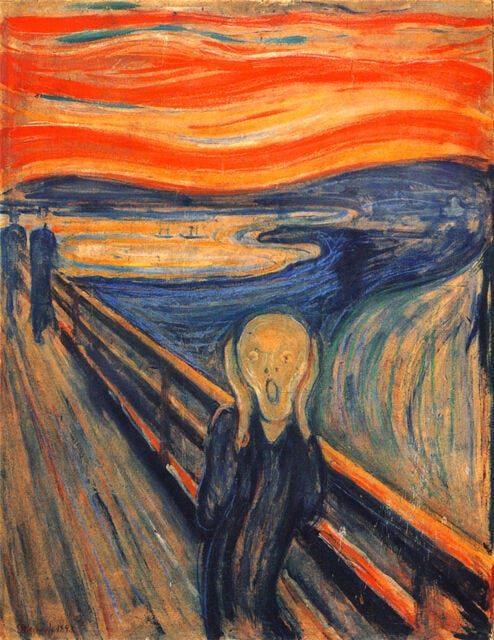

And then—those paintings! Those paintings of Edvard Munch! What precise visionary testaments of the soul's private hells and salty torture chambers! Brushed and slapped on mammoth canvases: paint streaked, striped, pasted, daubed, even squeezed directly out of the tubes! Paintings scratched, combed, gouged; feverishly worked paintings paintings of dissolving faces, ghoulish, madly staring, sunken-eyed creatures; putrefying corpses; emaciated, consumptive, sick, dying, wounded, bloodied bodies painted with, oh, what ferocity and sureness of expression, and what unexpected tenderness! I recognized them all. Oh, how did he know? How did he know the tortured, crying, crippled figures of my dreams?

One hundred and one years have passed since Munch painted his first great soul picture, The Sick Child. Perhaps now we can begin to allow ourselves to feel the depths of anguish in this work and the pothos, or nostalgia—for soul, behind it. Only a very few of his contemporaries could. But how glad I was to find his paintings! Immediately, he became a teacher for me, a soul guide, as did the Czech poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, whom I had recently discovered. How else could I have made it through six years of clinical psychology at the University of Oslo? Rilke and Munch were older soul brothers, telling me about the wolves I would meet in the forest, pointing out secret paths known only to initiates in the brotherhood of dark pain. Through them I began to trust my own sense of soul, to believe in the value and the nobility of the imagination, to dare to own experiences previously locked out in shame and humiliation. And then a strange thing happened. When I began to own my own soul life, I also began to see that it wasn't only mine. There was another dimension which didn't really belong to me. What freedom! To discover that I was also Everyman, Everywoman! The same currents of soul flowing through me as through the person walking beside me. We meet in this river—not the petty personal one in which so many schools of psychology get caught—but the bigger one, the greater river.

Archetypal psychology shares the concern for soul that Edvard Munch expressed. Archetypal psychology can move us to see things from the perspective of soul—to see the world ensouled and alive from end to end and to give first place to soul in our lives and psychologies. But the work of artists like Munch also contributes to the self-discovery and individuation of archetypal psychology itself. Great art does this because there is a transhis-torical dimension of the soul. The concerns of the soul are not bound by time, nor should they be allowed to be the exclusive domain of psychologists. Even the subjects of history become subjects of soul—when they have been touched by imagination.